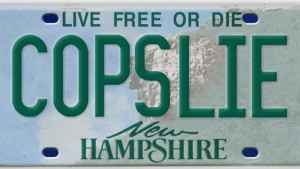

If the car driving in front of you has a picture of the confederate flag on its license plate, to whom should the speech be attributed, the driver or the state issuing the plate? Is the answer the same if the text of the vanity plate says “COPSLIE”? Last week, the U.S. Supreme Court partially answered those questions.

In Walker v. Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV), the Court considered the threshold issue of whether specialty license plate images like the confederate flag design the Sons of Confederate Veterans proposed to include as an option in Texas constituted government or private speech. If the image constitutes “government speech,” then the state has the legal right to regulate the message because it is attributable to the state. If, however, the license plate image constitutes private speech, as argued by the petitioner and supported by the ACLU in an amicus brief, then the government cannot engage in viewpoint discrimination by allowing some designs while prohibiting others.

In a 5-4 ruling, the United States Supreme Court held that Texas’ specialty license plate designs “constitute government speech, and thus Texas was entitled to refuse to issue plates featuring SCV’s proposed design…The fact that private parties take part in the design and propagation of a message does not extinguish the governmental nature of the message or transform the government’s role into that of a mere forum-provider.”

What does this mean for the many customized alphanumeric messages using numbers and letters that grace New Hampshire vanity plates? Nothing directly.

Unlike the Texas system through which groups apply to create speciality plates with customized plate images, NH drivers cannot pay the State to create additional license plate designs—so if you don’t like the Old Man of the Mountain, Veterans, or “moose” park plate designs, you are out of luck. In the Walker decision, the Court specifically stated that its ruling that specialized license plates constitute government speech applies only to the images on the plate, not to driver-created wording. Thus, the question of whether customizable messages on license plates constitutes private or government speech has been reserved for another day.

So are NH drivers limited only by their imaginations and the constraint of 7 characters when crafting vanity plates? Not quite.

Before 2014, one relevant DMV regulation prohibited vanity car license plates “which a reasonable person would find offensive to good taste.” This regulation was put to the test when the DMV rejected petitioner’s license plate “COPSLIE” (speech critical of the government) and then accepted the license plate “GR8GOVT” (speech praising the government). The ACLU filed a “friend-of-the-court” brief in the case arguing that this regulation violated Part I, Article 22 of the New Hampshire Constitution.

The NH Supreme Court agreed with our position that the regulation, on its face “violates the right to free speech guaranteed by Part I, Article 22 of the State Constitution …. [b]ecause the ‘offensive to good taste’ standard is not susceptible of objective definition, the restriction grants DMV officials the power to deny a proposed vanity registration plate because it offends particular officials’ subjective idea of what is ‘good taste.’” In short, because the regulation was vague, it allowed DMV officials to unconstitutionally engage in viewpoint discrimination by banning speech on license plates that expresses any point of view with which the DMV disagrees.

Since the ruling, the NH DMV changed the relevant regulation and now lists several specific prohibitions, including plates that “refer to” or are “associated with “racial, ethnic, religious, gender or sexual orientation hatred or bigotry.” This regulation raises First Amendment concerns because it allows DMV personnel reviewing vanity plate applications to discriminate on the basis of viewpoint. For example, a registrant could obtain the license plate “ILUVGOD,” but could be denied the license plate “IH8GOD.”

While these NH regulations are less likely to be susceptible to a vagueness challenge, they do constitute government regulation of speech the NH Supreme Court “assumed without deciding” was private speech on government property. Does Walker uphold this kind of blatant viewpoint discrimination? We don’t think so.

The customized messages NH drivers create when purchasing vanity plates are distinguishable from the customized images that the Supreme Court held constitute government speech in Texas. Walker says the First Amendment does not allow citizens to force the government to decorate government property in an offensive manner even if the government invites its citizens to submit decoration ideas. However, when the State invites its citizens onto government property to speak using a 7-character customized vanity plate message, it has created a public forum and therefore cannot discriminate based on the speaker’s viewpoint without violating the First Amendment.

NH’s Supreme Court has already assumed that if you drive by a car with the plate “COPSLIE,” it is the driver, not NH, that is speaking. We agree. And this means that the NH DMV shouldn’t be engaging in viewpoint discrimination on license plates. Period.

by Elizabeth Velez, NHCLU Legal Intern