Union Leader

December 29, 2015

During the most recent Republican debate, Donald Trump offered a simplistic strategy for fighting ISIS: Close off “areas” of the Internet. While it’s easy to mock such a solution from the Republican frontrunner, Hillary Clinton should also have to answer for her statements that call into question her handle on digital privacy and security and how they protect core civil liberties.

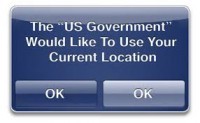

During the most recent Democratic debate, Clinton presented her plan to protect the nation from terrorist attack. Her strategy calls for a public-private partnership between the federal intelligence, homeland security, defense, and law enforcement agencies and the tech community. What exactly Clinton is proposing isn’t clear, but we should be very wary of proposals that turn Silicon Valley into an arm of the national security state.

In recent months, lawmakers have suggested that tech companies should, voluntarily or through a mandate, work to weaken the encryption of the mobile devices they produce and the communications that flow over their networks. Clinton understands that building “back doors,” or a way to access a device or software program that bypasses security mechanisms, has “important implications for security and civil liberties.” But she also doesn’t want “impenetrable encryption” to become the industry norm, despite increasing demand by the public to ensure the security of their electronic information.

The major problem for Hillary Clinton though is that strong encryption is essential to our security. When technology companies create back doors for law enforcement agencies to exploit, the weakness isn’t just available to the good guys when acting lawfully. It’s a weakness that any and all adversaries can find and use for their nefarious purposes. Inserting back doors into software and hardware is like putting locks and bars on all your windows and doors but leaving the basement window unlocked. Eventually a determined opponent will find it and make you pay for your mistake.

Furthermore, it won’t stop terrorists from exploiting encrypted communications apps and devices made overseas. Deliberately inserting security vulnerabilities into American devices and software, however, would harm the U.S. tech industry’s competitiveness both domestically and internationally. What intelligent consumer would knowingly purchase insecure devices that cannot protect their sensitive information from malicious actors, who have the expertise to steal their identity, raid their bank accounts, or ruin their reputations by publishing embarrassing things on the Web?

In the aftermath of the Paris and San Bernardino atrocities, these policies may appear like a wise and necessary shift toward emphasizing security over liberty, particularly when compared with Trump’s proposal. But such a judgment would be mistaken. These prescriptions are dangerous precisely because they sound reasonable, but they are just as infeasible and absurd as Trump’s idea for a partial Internet shutdown.

Worse, they could happen, and we’d all be less safe and free as a consequence. If Hillary Clinton really wants to protect the American people, she should become an encryption evangelist, not an equivocator.

By Devon Chaffee, Executive Director, ACLU of New Hampshire